Scientology

| Part of a series on |

| Scientology |

|---|

|

|

| Controversies |

| More |

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by the American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It is variously defined as a cult, a business, a religion, or a scam.[11] Hubbard initially developed a set of ideas that he called Dianetics, which he represented as a form of therapy. An organization that he established in 1950 to promote it went bankrupt, and Hubbard lost the rights to his book Dianetics in 1952. He then recharacterized his ideas as a religion, likely for tax purposes, and renamed them Scientology.[7][12][13] By 1954, he had regained the rights to Dianetics and founded the Church of Scientology, which remains the largest organization promoting Scientology. There are practitioners independent of the Church, in what is referred to as the Free Zone. Estimates put the number of Scientologists at under 40,000 worldwide.

Key Scientology beliefs include reincarnation, and that traumatic events cause subconscious command-like recordings in the mind (termed "engrams") that can be removed only through an activity called "auditing". A fee is charged for each session of "auditing". Once an "auditor" deems an individual free of "engrams" they are given the status of "clear". Scholarship differs on the interpretation of these beliefs: some academics regard them as religious in nature; other scholars regard them as merely a means of extracting money from Scientology recruits. After attaining "clear" status, adherents can take part in the Operating Thetan levels, which require further payments. The Operating Thetan texts are kept secret from most followers; they are revealed only after adherents have typically given hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Scientology organization.[14] Despite its efforts to maintain the secrecy of the texts, they are freely available on various websites, including at the media organization WikiLeaks.[15][16] These texts say past lives took place in extraterrestrial cultures.[17] They involve an alien called Xenu, described as a planetary ruler 70 million years ago who brought billions of aliens to Earth and killed them with thermonuclear weapons. Despite being kept secret from most followers, this forms the central mythological framework of Scientology's ostensible soteriology.[18] These aspects have become the subject of popular ridicule.

Since its formation, Scientology groups have generated considerable opposition and controversy. This includes deaths of practitioners while under Church of Scientology care, several instances of extensive criminal activities, and allegations by former adherents of exploitation and forced abortions. In the 1970s, Hubbard's followers engaged in a program of criminal infiltration of the U.S. government, resulting in several executives of the organization being convicted and imprisoned for multiple offenses by a U.S. federal court. Hubbard himself was convicted of fraud in absentia by a French court in 1978 and sentenced to four years in prison.[19] In 1992, a court in Canada convicted the Scientology organization in Toronto of spying on law enforcement and government agencies and criminal breach of trust, later upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.[20][21] The Church of Scientology was convicted of fraud by a French court in 2009, a judgment upheld by the supreme Court of Cassation in 2013.[22]

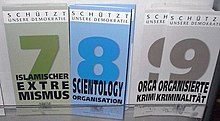

The Church of Scientology has been described by government inquiries, international parliamentary bodies, scholars, law lords, and numerous superior court judgments as both a dangerous cult and a manipulative profit-making business.[29] Numerous scholars and journalists have observed that profit is the primary motivating goal of the Scientology organization.[30] Following extensive litigation in numerous countries,[31][32] the organization has managed to attain a legal recognition as a religious institution in some jurisdictions, including Australia,[33][34] Italy,[32] and the United States.[35] Germany classifies Scientology groups as an anti-constitutional sect,[36][37] while the French government classifies the group as a dangerous cult.[38][39]

Definition and classification

The sociologist Stephen A. Kent views the Church of Scientology as "a multifaceted transnational corporation, only one element of which is religious".[40] In his history of the Church of Scientology, the scholar Hugh Urban describes Scientology as a "huge, complex, and multifaceted movement".[41]

Government inquiries, international parliamentary bodies, scholars, law lords, and numerous superior court judgments describe Scientology both as a dangerous cult and as a manipulative profit-making business. These institutions and scholars state that Scientology is not a religion.[42][43][44]

Scientology has experienced multiple schisms during its history.[45] While the Church of Scientology was the original promoter of the movement, various independent groups have split off to form independent Scientology groups. Referring to the "different types of Scientology", the scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggests it was appropriate to talk about "Scientologies".[46]

Urban describes Scientology as representing a "rich syncretistic blend" of sources, including elements from Hinduism and Buddhism, Thelema, new scientific ideas, science-fiction, and from psychology and popular self-help literature available by the mid-20th century.[47] The ceremonies, structure of the prayers, and minister attire suggested by Hubbard reflect his own Protestant traditions.[48]

Hubbard claimed that Scientology was "all-denominational",[49] and members of the Scientology organization are not prohibited from active involvement in religions.[50] Scholar of religion Donald Westbrook encountered members who also practiced Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, and the Nation of Islam; one was a Baptist minister.[49] In practice, however, Westbrook noted that most Church members consider Scientology to be their only commitment, and the deeper their involvement became, the less likely they were to continue practicing other traditions.[49]

Debates over classification

Debate as to whether Scientology should be regarded as a cult, a business, a scam, or a religion has continued over many years.[51] Many Scientologists consider it to be their religion.[52] Its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, presented it as a religion,[53] but the early history of the Scientology organization, and Hubbard's policy directives, letters, and instructions to subordinates, indicate that his motivation for doing so was as a legally pragmatic move to minimize his tax burden and escape the possibility of prosecution.[6][54] In many countries, the Church of Scientology has engaged in extensive litigation to secure recognition as a tax-exempt religious organization,[55] and it has managed to obtain such a status in a few jurisdictions, including the United States, Italy, and Australia.[43][56] The organization has not received recognition as a religious institution in the majority of countries in which it operates.[57]

An article in the magazine TIME, "The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power", describes Scientology as a ruthless global scam.[1] The Church of Scientology's attempts to sue the publishers for libel and to prevent republication abroad were dismissed.[58] Scholarship in psychology and skepticism supports this view of Scientology as a confidence trick to obtain money from its targets.[6][59] The scholar Benjamin Beit-Hallahmi observes that "the majority of activities conducted by Scientology and its many fronts and subsidiaries involve the marketing of secular products."[6] In a report by the European Parliament, it is observed that the group "is a cool, cynical, manipulating business and nothing else."[5]

Scholars and journalists note that profit is the primary motivating goal of Hubbard's Scientology groups.[30] Those making this observation have often referred to a governing financial policy issued by Hubbard that is to be obeyed by all Scientology organization staff members,[60] which includes the following [uppercase in original]:[61]

Make sure that lots of bodies move through the shop...A. MAKE MONEY. ... J. MAKE MONEY. K. MAKE MORE MONEY. L. MAKE OTHER PEOPLE PRODUCE SO AS TO MAKE MONEY...However you get them in or why, just do it.

Some scholars of religion have referred to Scientology as a religion.[62] The sociologist Bryan R. Wilson compares Scientology with 20 criteria that he associated with religion and concludes that the movement could be characterised as such. [63] Wilson's criteria include: a cosmology that describes a human reality beyond terrestrial existence; ethics and behavior teachings that are based on this cosmology; prescribed ways for followers to connect with spiritual beings; and a congregation that believes in and helps spread its teachings.[64] Allan W. Black analysed Scientology through the seven "dimensions of religion" set forward by the scholar Ninian Smart and also decided that Scientology met those criteria for being a religion.[65] The sociologist David V. Barrett noted that there was a "strong body of evidence to suggest that it makes sense to regard Scientology as a religion",[66] while scholar of religion James R. Lewis comments that "it is obvious that Scientology is a religion".[67] The scholar Mikael Rothstein observes that the Scientology "is best understood as a devotional cult aimed at revering the mythologized founder of the organization".[68]

Numerous religious studies scholars have described Scientology as a new religious movement.[69] Various scholars have also considered it within the category of Western esotericism,[70] while the scholar of religion Andreas Grünschloß noted that it was "closely linked" to UFO religions,[71] as science-fiction themes are evident in its theology.[72] Scholars have also varyingly described it as a "psychotherapeutically oriented religion",[73] a "secularized religion",[74] a "postmodern religion",[75] a "privatized religion",[76] and a "progressive-knowledge" religion.[77] According to scholar of religion Mary Farrell Bednarowski, Scientology describes itself as drawing on science, religion, psychology and philosophy but "has been claimed by none of them and repudiated, for the most part, by all".[78]

Government bodies and other institutions maintain that the Scientology organization is a commercial business that falsely claims to be religious,[79] or alternatively a form of therapy masquerading as religion. [80] The French government characterises the movement as a dangerous cult, and the German government monitors it as an anti-democratic sect.[36][37][38][39]

The notion of Scientology as a religion is strongly opposed by the anti-cult movement.[81] Its claims to a religious identity have been particularly rejected in continental Europe.[56] Grünschloß writes that labelling Scientology a religion does not mean that it is "automatically promoted as harmless, nice, good, and humane".[82] The multi-faceted nature of the Church of Scientology that includes pedagogy, communication theories, management principles and methods for a healthy living discombobulated many observers when it first started. Dericquebourg comments that the same things can be found in established churches.[83]

Etymology

The word Scientology, as coined by Hubbard, is a derivation from the Latin word scientia ("knowledge", "skill"), which comes from the verb scīre ("to know"), with the suffix -ology, from the Greek λόγος lógos ("word" or "account [of]").[84][85] Hubbard claimed that the word "Scientology" meant "knowing about knowing or science of knowledge".[86] The name "Scientology" deliberately makes use of the word "science",[87] seeking to benefit from the "prestige and perceived legitimacy" of natural science in the public imagination.[88] In doing so, Scientology has been compared to religious groups like Christian Science and the Science of Mind, which employed similar tactics.[89]

The term "Scientology" had been used in published works at least twice before Hubbard.[86] In The New Word (1901), poet and lawyer Allen Upward first used scientology to mean blind, unthinking acceptance of scientific doctrine (compare scientism).[90][91] In 1934, philosopher Anastasius Nordenholz published Scientology: Science of the Constitution and Usefulness of Knowledge, which used the term to mean the science of science.[92]: 116–9 [93] It is unknown whether Hubbard was aware of either prior usage of the word.[92]: 116–9 [94]: 111

History

As the 1950s developed, Hubbard saw the advantages of having his Scientology movement legally recognised as a religion.[95] In an April 1953 letter to Helen O'Brien, his US business manager, he proposed that Scientology should be transformed into a religion: "We don't want a clinic. We want one in operation but not in name...It is a problem of practical business. I await your reaction on the religion angle".[96] In reaction to a series of arrests of his followers, and the prosecution of Hubbard's Dianetics foundation for teaching medicine without a license, in December 1953 Hubbard incorporated three organizations – Church of American Science, Church of Scientology, and Church of Spiritual Engineering.[54][97] In 1959, Hubbard purchased Saint Hill Manor in East Grinstead, Sussex, United Kingdom, which became the worldwide headquarters of the Church of Scientology and his personal residence. With the organization often under heavy criticism, it adopted strong measures of attack in dealing with its critics.[98]

In 1966, the organization established the Guardian's Office (GO), a department devoted to undermining those hostile towards Scientology.[99] The GO launched an extensive program of countering negative publicity, gathering intelligence, and infiltrating organizations.[100] In "Operation Snow White", the GO infiltrated the IRS and numerous other government departments and stole tens of thousands of documents pertaining to the Church, politicians, and celebrities.[101] In July 1977, the FBI raided Church premises in Washington, DC, and Los Angeles, revealing the extent of the GO's infiltration into government departments and other groups.[102] Eleven officials and agents of the Church were indicted; in December 1979, they were sentenced to between 4 and 5 years each and individually fined $10,000 (equivalent to $42,000 in 2023).[103][104] Among those found guilty was Hubbard's then-wife, Mary Sue Hubbard.[101] Public revelation of the GO's activities brought widespread condemnation of the Church.[103]

In 1967, Hubbard established a new group, the Sea Organization or "Sea Org", the membership of which was drawn from the most committed members of the Scientology organization.[105] By 1981, the 21-year-old David Miscavige, who had been one of Hubbard's closest aides in the Sea Org, rose to prominence.[55] Hubbard died at his ranch in Creston, California, on January 24, 1986, and David Miscavige succeeded Hubbard as head of the Church.[106][107] In 1993, the Internal Revenue Service dropped all litigation against the Scientology organization and recognized it as a religious institution.[108]

Beliefs and practices

Hubbard lies at the core of Scientology and his writings remain the source of its ideas and practices.[109] Sociologist of religion David G. Bromley describes Scientology as Hubbard's "personal synthesis of philosophy, physics, and psychology".[110] Hubbard claimed that he developed his ideas through research and experimentation, rather than through revelation from a supernatural source.[111] He published hundreds of articles and books over the course of his life.[112] Scientologists regard his writings on Scientology as scripture.[113] Much basic information about the Scientology belief system is kept secret from most practitioners.[114] The scholar and historian of Scientology Hugh Urban observes that:[115]

A great many aspects of Scientology are shrouded in layers of secrecy, concealment, obfuscation, and/or dissimulation.

In Scientology Hubbard's work is regarded as perfect, and no elaboration or alteration is permitted.[116] Hubbard described Scientology as an "applied religious philosophy", because, according to him, it consists of a metaphysical doctrine, a theory of psychology, and teachings in morality.[117] Hubbard incorporated a variety of hypnotic techniques in Scientology auditing and courses.[118] These are used as a means to create dependency and obedience in followers.[119] Hubbard said of the beliefs that:[120][121][122]

A civilization without insanity, without criminals and without war; where the world can prosper and honest beings can have rights, and where man is free to rise to greater heights, are the aims of Scientology.

Hubbard developed thousands of neologisms during his lifetime.[116] The nomenclature used by the movement is termed "Scientologese" by members.[123] Scientologists are expected to learn this specialist terminology, the use of which separates followers from non-Scientologists.[116] The Scientology organization refers to its practices as "technology", a term often shortened to "Tech".[124] Scientologists stress the "standardness" of this "tech", by which they express belief in its infallibility.[125] The Church's system of pedagogy is called "Study Tech" and is presented as the best method for learning.[126] Scientology teaches that when reading, it is very important not to go past a word one does not understand. A person should instead consult a dictionary as to the meaning of the word before progressing, something Scientology calls "word clearing".[127]

According to Scientology texts, its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to scientific laws.[128] Blind belief is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.[128] Adherents are encouraged to validate the practices through their personal experience.[128] Hubbard put it this way: "For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, 'did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn't it?'"[128] Many Scientologists avoid using the words "belief" or "faith" to describe how Hubbard's teachings impacts their lives, preferring to say that they "know" it to be true.[129]

Auditing

The central practice of Scientology is an activity known as "auditing". It takes place with two Scientologists — one is the "auditor" who asks questions, and the subject is termed the "preclear". The stated purpose is to help the subject to remove their mental traumas (ostensible recordings in the mind which Hubbard termed "engrams").[130] Scholarship in clinical psychology demonstrates that the purpose of auditing is to induce a light hypnotic state and to create dependency and obedience in the subject.[118] When deemed free of engrams they are given the status of "clear", and then continue doing further auditing until they are deemed to have reached the level Operating Thetan. Hubbard assigns vitality, good health and increased intelligence to those who are given the status of "clear", having removed the source of their "psychosomatic illnesses".[130] The further status of Operating Thetan (OT) is posited as complete spiritual freedom in which one is able to do anything one chooses, create anything, go anywhere — an idea which has appealed to many.[131]

The scholar Hugh Urban describes the supernatural powers promoted as being gained by an Operating Thetan as:[132]

The liberated thetan could even freely create a personal paradise, populating it with heavenly beings and infinite pleasures at will. ... As such, the thetan who truly realized his power to create and destroy universes would in effect be "beyond God". ... The thetan has been deceived into worshipping such a God by mainstream religion and so forgotten its own godlike power to create and destroy universes.

— Hugh Urban in The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion

The prices to undertake a full course of auditing with the Church of Scientology are not often advertised publicly.[133] As of 2011 it can easily cost $400,000 to do the entirety of Scientology's "Bridge to Total Freedom" (equivalent to $542,000 in 2023).[134][104] In a 1964 letter, Hubbard stated that a 25-hour block of auditing should cost the equivalent of "three months' pay for the average middle class working individual."[133] In 2007, the fee for a 12 and a half hour block of auditing at the Tampa Org was $4000 (equivalent to $5,880 in 2023).[135][104] The Scientology organization is often criticized for the prices it charges for auditing,[135] and examinations of the group have indicated that profit is the group's primary purpose.[136] Hubbard stated that charging for auditing was necessary because the practice required an exchange, and should the auditor not receive something for their services it could harm both parties.[135]

During auditing, a device called an electropsychometer (E-meter) is used.[137] Scientology's primary road map for guiding a person through the sequential steps to attain Scientology's concepts of "clear" and OT is The Bridge to Total Freedom, a large chart enumerating every step in sequence.[138] The steps past "clear" are kept secret from most Scientologists and include the founding myth that seeks to explain Scientology doctrine.[139][140]

Soul

Hubbard taught that there were three parts of man: the spirit, mind, and body.[141] The first of these is a person's inner self which he calls a "thetan".[142] It is akin to the idea of the soul or spirit found in religious traditions.[143] Hubbard stated that "the thetan is the person. You are YOU in a body."[144] Hubbard referred to the physical universe as the MEST universe, meaning "Matter, Energy, Space and Time", which includes your body.[145] Scientologists believe that thetans can exteriorize; leave their body.[146] The thetan is considered an immortal being who has been reincarnated many times over.[147] Someone who has died is said to have "dropped the body".[148] Scientology refers to the existence of a Supreme Being, but practitioners are not expected to worship it.[149] No intercessions are made to seek this being's assistance in daily life.[150]

Space opera and the Wall of Fire

The mythological framework which forms the basis for what Scientologists view as the system's path to salvation is the story of Xenu.[151] Reflecting a strong science-fiction theme within its theology,[72] Scientology's teachings make reference to "space opera", a term denoting events in the distant past in which "spaceships, spacemen, [and] intergalactic travel" all feature.[152]

Hubbard wrote about a great catastrophe that took place 75 million years ago.[77] According to this story, 75 million years ago there was a Galactic Confederacy of 76 planets ruled over by a leader called Xenu. The Confederacy was overpopulated and Xenu transported millions of aliens to earth and killed them with hydrogen bombs.[153] The thetans of those killed were then clustered together and implants were inserted into them, designed to kill any body that these thetans would subsequently inhabit should they recall the event of their destruction.[154] After the massacre, several of the officers in Xenu's service rebelled against him, ultimately capturing and imprisoning him.[155] Hubbard claimed to have discovered the Xenu myth in December 1967, having taken the "plunge" deep into his "time track".[156] Scientology teaches that attempting to recover this information from the "time track" typically results in an individual's death, caused by the presence of Xenu's implants, but that because of Hubbard's "technology" this death can be avoided.[157]

The Scientology organization says that learning the Xenu myth can be harmful for those unprepared for it,[159] and the documents discussing Xenu are kept secret from most members.[160] The teachings about Xenu were later leaked by ex-members,[161] becoming a matter of public record after being submitted as evidence in court cases.[162][163] They are now widely available online.[164] Members who have been given the teachings routinely deny these teachings exist.[165] Hubbard however talked about Xenu on several occasions,[166] the Xenu story bears similarities with some of the science-fiction stories Hubbard published,[167] and substantial themes from the Xenu story are in Hubbard's book Scientology – A History of Man.[168]

The Operating Thetan levels

The degrees above the level of Clear are called "Operating Thetan" or OT.[169] Hubbard described there being 15 OT levels, although he had only completed eight of these during his lifetime.[170] OT levels nine to 15 have not been reached by any Scientologist.[171] In 1988 the Scientology organization stated that OT levels nine and ten would only be released when certain benchmarks in its expansion had been achieved.[172] The Church of Scientology has gone to considerable length to try to maintain the secrecy of the texts, but they remain widely available on the internet. This is partly due to litigation involving Scientology, whereby the Fishman Affidavit was leaked to the public.[7] Materials have also been passed on to other sources and made available by publishers such as the media organization WikiLeaks.[16]

To gain the OT levels of training, a member must go to one of the Advanced Organisations or Orgs, which are based in Los Angeles, Clearwater, East Grinstead, Copenhagen, Sydney, and Johannesburg.[173] Conservative estimates indicate that getting to OT VIII would require a minimum of payments to the Scientology organization of $350,000 to $400,000 (equivalent to $542,000 in 2023).[174][104] OT levels six and seven are only available at Clearwater.[175] The highest level, OT eight, is disclosed only at sea on the Scientology ship Freewinds, operated by the Flag Ship Service Org.[176][177] Scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggested that the status of a person's level creates an internal class system within the Scientology organization.[178]

The Scientology organization claims that the material taught in the OT levels can only be comprehended once its previous material has been mastered and is therefore kept confidential until a person reaches the requisite level.[179] Higher-level members typically refuse to talk about the contents of these OT levels.[180] Those progressing through the OT levels are taught additional, more advanced auditing techniques;[181] one of the techniques taught is a method of auditing oneself,[182] which is the necessary procedure for reaching OT level seven.[175]

Ethics

Scientology has its own unique definitions for ethics and procedures for justice. According to scholar Stephen Kent, "The purpose of Scientology ethics is to eliminate opponents, then eliminate people's interests in things other than Scientology. In this 'ethical' environment, Scientology would be able to impose its courses, philosophy, and 'justice system' – its so-called technology—onto society."[183]

Symbology

Hubbard created many symbolism concepts, including the eight dynamics, the ARC and KRC triangles, the "S and double triangle" symbol, the Scientology cross, and many others. Scientology celebrates seven calendar events including L. Ron Hubbard's birthday, Auditor's Day, and New Year's. There is a Sunday service which is primarily of interest for non-members and beginners. Weddings and funerals are also held.[68]

Psychiatry, psychology, psychosis

Scientology is vehemently opposed to psychiatry and psychology, and wants to replace them with its own methods.[184] The clinical and academic psychiatry community rejected Hubbard's theories in the early 1950s.[185] Hubbard and his early Dianetics organization were prosecuted for practicing medicine without a license in the early 1950s.[186]

Hubbard taught that psychiatrists were responsible for a great many wrongs in the world, saying that psychiatry has at various times offered itself as a tool of political suppression and that psychiatry was responsible for the ideology of Hitler, for turning the Nazis into mass murderers, and the Holocaust.[187] The Scientology organization operates the anti-psychiatry group Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), which operates Psychiatry: An Industry of Death, an anti-psychiatry museum.[187] Though Hubbard had stated psychosis was not something Scientology dealt with, after noticing many Scientologists were suffering breakdowns after using his techniques he created the Introspection Rundown, a brutal and inhumane method to allegedly solve psychotic episodes.[188]: 208–9 The rundown came under public scrutiny when in 1995 Scientologist Lisa McPherson suffered a mental breakdown and was removed from the hospital and held in isolation at a Church of Scientology for 17 days before she died.[189]: Part 2

Views on Hubbard

Scientologists view Hubbard as an extraordinary man, but do not worship him as a deity.[190] They regard him as the preeminent Operating Thetan who remained on Earth in order to show others the way to spiritual liberation,[116] the man who discovered the source of human misery and a technology allowing everyone to achieve their true potential.[191] Church of Scientology management frames Hubbard's physical death as "dropping his body" to pursue higher levels of research not possible with an Earth-bound body.[148]

Scientologists often refer to Hubbard affectionately as "Ron",[192] and many refer to him as their "friend".[193] The Scientology organization operates a calendar in which 1950, the year in which Hubbard's book Dianetics was published, is considered year zero, the beginning of an era. Years after that date are referred to as "AD" for "After Dianetics".[194] They have also buried copies of his writings preserved on stainless steel disks in a secure underground vault in the hope of preserving them against major catastrophes.[191] The Church of Scientology's view of Hubbard is presented in their hagiographical biography of him,[195] seeking to present him as "a person of exceptional character, morals and intelligence".[196] Critics of Hubbard and his organization claim that many of the details of his life as he presented it were false.[197] Every Scientology Org maintains an office set aside for Hubbard in perpetuity, set out to imitate those he used in life,[198] and will typically have a bust or large framed photograph of him on display.[199]

The Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is headquartered at "Gold Base" in Riverside County, California, where the highest Sea Org officials work,[200] and at "Flag Land Base" in Clearwater, Florida.[201] The organization operates on a hierarchical and top-down basis,[202] being largely bureaucratic in structure.[203] It claims to be the only true voice of Scientology.[204] The internal structure of Scientology organizations is strongly bureaucratic with a focus on statistics-based management.[205] Organizational operating budgets are performance-related and subject to frequent reviews.[205]

By 2011, the organization was claiming over 700 centres in 65 countries.[206] Smaller centres are called "missions".[207] The largest number of these are in the U.S., with the second largest number being in Europe.[208] Missions are established by missionaries, who are referred to as "mission holders".[209] Members can establish a mission wherever they wish but must fund it themselves; the missions are not financially supported by the central organization.[210] Mission holders must purchase all of the necessary material from the central Church of Scientology; as of 2001, the Mission Starter Pack cost $35,000 (equivalent to $60,200 in 2023).[211][104]

Each mission or Org is a corporate entity, established as a licensed franchise, and operating as a commercial company.[214] Each franchise sends part of its earnings, which have been generated through beginner-level auditing, to the International Management.[215] Bromley observed that an entrepreneurial incentive system pervades the organization, with individual members and organisations receiving payment for bringing in new people or for signing them up for more advanced services.[216] The individual and collective performances of different members and missions are gathered, being called "stats".[217] Performances that are an improvement on the previous week are termed "up stats"; those that show a decline are "down stats".[218] According to leaked tax documents, the Church of Scientology International and Church of Spiritual Technology in the US had a combined $1.7 billion in assets in 2012, in addition to annual revenues estimated at $200 million a year.[219]

Internal organization

The Sea Org is the organization's primary management unit,[216] containing the highest ranks in its hierarchy.[205] Its members are often recruited from the children of existing Scientologists,[220] and sign up to a "billion-year contract" to serve the Church.[221] Kent described that for adult Sea Org members with minor children, their work obligations took priority, damaged parent-child relations, and has led to cases of severe child neglect and endangerment.[222]

The Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF) is the Church of Scientology's disciplinary program,[223] where Sea Org members deemed to have seriously deviated from its teachings are placed.[224][225] They will often face a hearing, the "Committee of Evidence", which determines if they will be sent to the RPF.[226] The RPF operates out of several locations.[227] It involves a daily regimen of five hours of auditing or studying, eight hours of work, often physical labor, such as building renovation, and at least seven hours of sleep.[225] Critics have condemned RPF practices for violating human rights;[223] and criticized the Scientology organization for placing children as young as twelve into the RPF, engaging them in forced labor and denying access to their parents, violating Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[183] The RPF has contributed to characterisations of the organization as a cult.[228]

The Office of Special Affairs or OSA (formerly the Guardian's Office) is a department of the Church of Scientology which has been characterized as a non-state intelligence agency.[229][230][231] It has targeted critics of the organization for "dead agent" operations, which is mounting character assassination operations against perceived enemies.[232] A 1990 article in the Los Angeles Times reported that in the 1980s the Scientology organization more commonly used private investigators, including former and current Los Angeles police officers, to give themselves a layer of protection in case embarrassing tactics were used and became public.[233] The International Association of Scientologists operates to advance the cause of the Scientology organization and its members across the world.[234]

Promotional material

The Scientology organization employs a range of media to promote itself and attract converts.[235] Hubbard promoted Scientology through a vast range of books, articles, and lectures.[116] It publishes several magazines, including Source, Advance, The Auditor, and Freedom.[112] It has established a publishing press, New Era,[236] and the audiovisual publisher Golden Era.[237] It has also used the Internet for promotional purposes,[238] and employed advertising to attract potential converts, including in high-profile locations such as television ads during the 2014 and 2020 Super Bowls.[239]

The organization has long used celebrities as a means of promoting itself, starting with Hubbard's "Project Celebrity" in 1955 and followed by its first Scientology Celebrity Centre in 1969.[240] The Celebrity Centre headquarters is in Hollywood; other branches are in Dallas, Nashville, Las Vegas, New York City, and Paris.[241] In 1955, Hubbard created a list of 63 celebrities targeted for conversion to Scientology.[242] Prominent celebrities who have joined the organization include John Travolta, Tom Cruise, Kirstie Alley, Nancy Cartwright, and Juliette Lewis.[243] The Church uses celebrity involvement to make itself appear more desirable.[244] Other new religious movements have similarly pursued celebrity involvement such as the Church of Satan, Transcendental Meditation, ISKCON, and the Kabbalah Centre.[245]

Social outreach

Several Scientology organizations promote the use of Scientology practices as a means to solve social problems. Scientology began to focus on these issues in the early 1970s. The Church of Scientology developed outreach programs that say they aim to fight drug addiction, illiteracy, learning disabilities and criminal behavior. They have been presented to schools, businesses and communities as secular techniques based on Hubbard's writings.[246] They have been described as part of the Scientology organization's "war" against the discipline of psychiatry.[247] Some critics regard this outreach as merely a public relations exercise.[124]

Launched in 1966, Narconon is its drug rehabilitation program, which employs Hubbard's theories about drugs and treats addicts through auditing, exercise, saunas, vitamin supplements, and healthy eating.[248] It has been described as a front group for recruiting into Scientology.[249][250][251] Criminon is the organization's criminal rehabilitation programme.[110][252] Its Applied Scholastics program, established in 1972, employs Hubbard's pedagogical methods to help students.[253][254] The Way to Happiness Foundation promotes a moral code written by Hubbard, to date translated into more than 40 languages.[254] Narconon, Criminon, Applied Scholastics, and The Way to Happiness operate under the management banner of Association for Better Living and Education.[255][256] The World Institute of Scientology Enterprises (WISE) applies Scientology practices to business management.[40][254] The most prominent training supplier to make use of Hubbard's technology is Sterling Management Systems.[254]

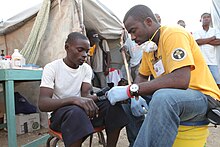

Hubbard devised the Volunteer Minister Program in 1973.[257] They offer help and counselling to those in distress; this includes the Scientological technique of providing "assists".[257] After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in New York City, Volunteer Ministers were on the site of Ground Zero within hours of the attack;[258] they subsequently went to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.[41] Accounts of the Volunteer Ministers' effectiveness have been mixed, and touch assists are not supported by scientific evidence.[259][260][261]

Responses to opponents

The Scientology organization regards itself as the victim of media and governmental persecution,[262] and the scholar of religion Douglas Cowan observed that "claims to systematic persecution and harassment" are part of the internal culture.[263] In turn, Urban noted the organization has "tended to respond very aggressively to its critics, mounting numerous lawsuits and at times using extralegal means to respond to those who threaten it."[262] The organization has often responded to criticism by ad hominem attacks.[264] Its approach to targeting critics has often generated more negative attention for their organization,[265] with Lewis commenting that it "has proven to be its own worst enemy" in this regard.[266]

It has a reputation for litigiousness stemming from its involvement in a large number of legal conflicts.[267] Barrett characterised the organization as "one of the most litigious religions in the world".[268] It has conducted lawsuits against governments, organizations, and individuals, both to counter criticisms made against it and to gain legal recognition as a religion.[269] J.P. Kumar, who studied the litigation, argued that victory was not always important to the organization; what was important was depleting the resources and energies of its critics.[270]

Suppressive persons and fair game

Those deemed hostile to the Church of Scientology, including ex-members, are labelled "suppressive persons" or SPs.[271] Hubbard maintained that 20 percent of the population would be classed as "suppressive persons" because they were truly malevolent or dangerous: "the Adolf Hitlers and the Genghis Khans, the unrepentant murderers and the drug lords".[272][273] If the organization declares that one of its members is an SP, all other members are forbidden from further contact with them, an act it calls "disconnection".[265] Any member breaking this rule is labelled a "potential trouble source" (PTS) and unless they swiftly cease all contact they can be labelled an SP themselves.[274][275][78]

In an October 1968 letter to members, Hubbard wrote about a policy called "fair game" which was directed at SPs and other perceived threats to the organization.[98][276] Here he stated that these individuals "may be deprived of property or injured by any means by any Scientologist without any discipline of the Scientologists. May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed".[271] Following strong criticism, the organization said that it formally ended Fair Game a month later, with Hubbard stating that he had never intended "to authorize illegal or harassment type acts against anyone."[277] Critics and some scholarly observers argue that its practices reflect that the policy remains in place.[278] It is "widely asserted" by former members that Fair Game is still employed;[279] Stacy Brooks, a former member of the internal Office of Special Affairs, stated in court that "practices which were formerly called 'Fair Game' continue to be employed, although the term 'Fair Game' is no longer used."[277]

Hubbard and his followers targeted many individuals as well as government officials and agencies, including a program of illegal infiltration of the IRS and other U.S. government agencies during the 1970s.[280][276] They also conducted private investigations, character assassination and legal action against the organization's critics in the media.[280]

The Scientology ethics and justice system regulates member behavior,[205] and Ethics officers are present in every Scientology organization. Ethics officers ensure "correct application of Scientology technology" and deal with "behavior adversely affecting a Scientology organization's performance", ranging from "errors" and "misdemeanors" to "crimes" and "suppressive acts", as those terms defined by Scientology.[225]

Free Zone and independent Scientology

The terms "Free Zone", "Freezone" and "Independent Scientology" are used by those who practice Scientology outside of the purview of the Church of Scientology. Free Zoners believe that Church of Scientology leadership has deviated from Hubbard's teachings, while asserting their own loyalty to Hubbard. The Church of Scientology is hostile to the Free Zone, and refers to such independent Scientologists as "squirrels", In 1983, the Advanced Ability Center was founded by David Mayo in California, but was successfully shut down by the Church of Scientology. Conversely, still operating in 2023 is Ron's Org in Europe, founded in 1984 by Bill Robertson as a loose grouping of independent centers rather than a centralized organization. Robertson coined the term "free zone" from Hubbard's space opera teachings. Since Robertson had said that he was channeling messages from the late Hubbard and had obtained OT levels above the eight offered by the Church of Scientology, many of the newer "indies" prefer to call themselves "independent scientologists" to distance themselves from Robertson.[281]

Controversies

Urban described the Church of Scientology as "the world's most controversial new religion",[41] while Lewis termed it "arguably the most persistently controversial" of contemporary new religious movements.[284] According to Urban, the organization had "a documented history of extremely problematic behavior ranging from espionage against government agencies to shocking attacks on critics of the organization and abuse of its own members."[285]

A first point of controversy was its response to its rejection by the psychotherapeutic establishment. Another was a 1991 Time magazine article about the organization, which responded with a major lawsuit that was rejected by the court as baseless early in 1992. A third is its religious tax status in the United States, as the IRS granted the organization tax-exempt status in 1993.[286]

It has been in conflict with the governments and police forces of many countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada,[287] France[288] and Germany).[289][1][290][291] It has been one of the most litigious religious movements in history, filing countless lawsuits against governments, organizations and individuals.[292]

Reports and allegations have been made, by journalists, courts, and governmental bodies of several countries, that the Church of Scientology is an unscrupulous commercial enterprise that harasses its critics and brutally exploits its members.[290][293] A considerable amount of investigation has been aimed at the organization, by groups ranging from the media to governmental agencies.[290][293]

The controversies involving the Church of Scientology, some of them ongoing, include:

- Criminal behavior by members of the organization, including the infiltration of the US Government.[1]

- Organized harassment of people perceived as enemies of the Church of Scientology.[1]

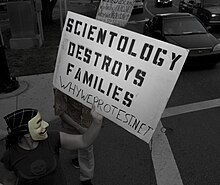

- Scientology's disconnection policy, in which some members are required to shun friends or family members who are "antagonistic" to the organization.[294][295]

- The death of Scientologist Lisa McPherson while in the care of the organization. Robert Minton sponsored the multimillion-dollar lawsuit against Scientology for the death of McPherson. In May 2004, McPherson's estate and the Church of Scientology reached a confidential settlement.[296]

- Attempts to legally force search engines to censor information critical of the Scientology organization.[297]

- Allegations the organization's leader David Miscavige beats and demoralizes staff, and that physical violence by superiors towards staff working for them is a common occurrence in the organization.[189][298] Scientology spokesman Tommy Davis denied these claims and provided witnesses to rebut them.[189]

Stephen A. Kent, a professor of sociology, has said that "Scientologists see themselves as possessors of doctrines and skills that can save the world, if not the galaxy."[299] As stated in Scientology doctrine: "The whole agonized future of this planet, every man, woman and child on it, and your own destiny for the next endless trillions of years depend on what you do here and now with and in Scientology."[300] Kent has described the Scientology ethics and justice system as "a peculiar brand of morality that uniquely benefited [the Church of Scientology] ... In plain English, the purpose of Scientology ethics is to eliminate opponents, then eliminate people's interests in things other than Scientology."[183]

Many former members have come forward to speak out about the organization and the negative effects its teachings have had on them, including celebrities such as Leah Remini. Remini spoke about her split from the Church of Scientology, saying that she still has friends within the organization whom she is no longer able to speak with.[301]

Throughout the early 1950s, adherents of Hubbard were arrested for practicing medicine without a license. In January 1951, the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners brought proceedings against the Dianetic Research Foundation on the charge of teaching medicine without a license. In January 1963 U.S. Marshals raided the Founding Church of Scientology in Washington.[186] Scientology social programs such as drug and criminal rehabilitation have also drawn both support and criticism.[302][303][304]

Hubbard's motives

Common criticisms directed at Hubbard was that he drew upon pre-existing sources and the allegation that he was motivated by financial reasons.[305] A number of Hubbard's letters and directives to his subordinates support the notion that he used religion as a façade for Scientology to maintain tax-exempt status[6] and avoid further prosecutions (a number of Dianetics or Scientology practitioners had already been arrested) for medical claims.[306] The IRS cited a statement frequently attributed to Hubbard that the way to get rich was to found a religion.[97] Many of Hubbard's science fiction colleagues, including Sam Merwin, Lloyd Arthur Eshbach and Sam Moscowitz, recall Hubbard raising the topic in conversation.[307][308][309] In 2006, Rolling Stone's Janet Reitman also attributed the statement to Hubbard, as a remark to science fiction writer Lloyd Eshbach and recorded in Eshbach's autobiography.[299]

Criminal behavior

In 1978, a number of Scientologists, including L. Ron Hubbard's wife Mary Sue Hubbard (who was second in command in the organization at the time), were convicted of perpetrating what was at the time the largest incident of domestic espionage in the history of the United States, called "Operation Snow White". This involved infiltrating, wiretapping, and stealing documents from the offices of Federal attorneys and the Internal Revenue Service.[310] L. Ron Hubbard was convicted in absentia by French authorities of engaging in fraud and sentenced to four years in prison.[19] The head of the French Church of Scientology was convicted at the same trial and given a suspended one-year prison sentence.[311]

An FBI raid on the Church of Scientology's headquarters revealed documentation that detailed Scientology's criminal actions against various critics of the organization. In "Operation Freakout", agents of the organization attempted to destroy Paulette Cooper, author of The Scandal of Scientology, an early book that had been critical of the movement.[312] Among these documents was a plan to frame Gabe Cazares, the mayor of Clearwater, Florida, with a staged hit-and-run accident. Nine individuals related to the case were prosecuted on charges of theft, burglary, conspiracy, and other crimes.

In 1988, Scientology president Heber Jentzsch and ten other members of the organization were arrested in Spain on various charges including illicit association, coercion, fraud, and labor law violations.[313] In October 2009, the Church of Scientology was found guilty of organized fraud in France.[314] The sentence was confirmed by the court of appeal in February 2012, and by the supreme Court of Cassation in October 2013.[315][22] In 2012, Belgian prosecutors indicted Scientology as a criminal organization engaged in fraud and extortion.[316][317][318] In March 2016, the Church of Scientology was acquitted of all charges, and demands to close its Belgian branch and European headquarters were dismissed.[319]

Organized harassment

Scientology has historically engaged in hostile action toward its critics; executives within the organization have proclaimed that Scientology is "not a turn-the-other-cheek religion".[320] Since the 1960s, Journalists, politicians, former Scientologists and various anti-cult groups have said that Scientology followers have engaged in organized hostility, harassment and threats, and Scientology has targeted these critics–almost without exception–for retaliation, in the form of lawsuits and public counter-accusations of personal wrongdoing. Many of Scientology's critics have also reported they were subject to threats and harassment in their private lives.[321][322]

According to a 1990 Los Angeles Times article, the Scientology organization had largely switched from using members to using private investigators, including former and current Los Angeles police officers, as this gives the organization a layer of protection in case investigators use tactics which might cause the organization embarrassment. In one case, the organization described their tactics as "LAPD sanctioned", which was energetically disputed by Police Chief Daryl Gates. The officer involved in this particular case of surveillance and harassment was suspended for six months.[233]

Journalist John Sweeney reported that "While making our BBC Panorama film Scientology and Me I have been shouted at, spied on, had my hotel invaded at midnight, denounced as a 'bigot' by star Scientologists, brain-washed – that is how it felt to me – in a mock up of a Nazi-style torture chamber and chased round the streets of Los Angeles by sinister strangers".[323]

Mistreatment of Members

A prominent ex-member who has spoken out about the Scientology organization's mistreatment of members and ex-members is Leah Remini. Remini is an American actress that has been involved with the Church of Scientology since childhood. She left in 2013. In 2015 she published a book entitled Troublemaker: Surviving Hollywood and Scientology where she recounts her experiences and events leading up to her leaving the organization.[324]

She also has produced a documentary television series on A&E entitled Leah Remini: Scientology and the Aftermath released in 2017 which aired for three seasons. In this series, she and her co-host Mike Rinder, who is also an ex-member, tell their experiences and interview numerous ex-members with similar. Leah Remini has been outspoken about her views on the Church of Scientology and has raised much awareness about some of the major issues within the church regarding treatment of children, exploitive money practices and mistreatments she has experienced.

As of August 2023, Leah has filed a lawsuit against the Church of Scientology. She alleges verbal, physical and sexual abuse was known and tolerated by the organization, and exploitive practices such as signing billion-year contracts with the organization. The main claims of the lawsuit are for psychological torture, defamation, surveillance, harassment, and intimidation experienced by her for years while a member, and as tactics used after she publicly left.[325]

Violation of auditing confidentiality

During the auditing process, the auditor collects and records personal information from the client.[326] While the Church of Scientology claims to protect the confidentiality of auditing records, the organization has a history of attacking and psychologically abusing former members using information culled from the records.[326] For example, a December 16, 1969, a Guardian's Office order (G. O. 121669) by Mary Sue Hubbard explicitly authorized the use of auditing records for purposes of "internal security".[327] Former members report having participated in combing through information obtained in auditing sessions to see if it could be used for smear campaigns against critics.[328][329]

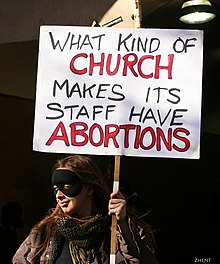

Allegations of coerced abortions

The Sea Org originally operated on vessels at sea where it was understood that it was not permitted to raise children on board the ships because "children hinder adults from performing their vital assignments". Women who became pregnant have stated that they had been "coercively persuaded" to undergo abortions in order to remain in the Sea Org.[330]

In 2003, The Times of India reported "Forced abortions, beatings, starvation are considered tools of discipline in this church".[331] A former high-ranking source reports that "some 1,500 abortions" have been "carried out by women in the Sea Organization since the implementation of a rule in the late 80s that members could not remain in the organization if they decided to have children". The source noted that "And if members who have been in the Sea Organization for, say, 10 years do decide to have kids, they are dismissed with no more than $1,000" as a severance package.[332]

Longtime member Astra Woodcraft left Scientology for good when the organization tried to pressure her to have an abortion.[333][334] Former Sea Org member Karen Pressley recounted that she was often asked by fellow Scientologists for loans so that they could get an abortion and remain in the Sea Org.[335][336][337] Scientology employee Claire Headley has said she "was forced to have (two) abortions to keep her job and was subjected to violations of personal rights and liberties for the purpose of obtaining forced labor".[338] Laura Ann DeCrescenzo reported she was "coerced to have an abortion" as a minor.[339]

In March 2009, Maureen Bolstad reported that women who worked at Scientology's headquarters were forced to have abortions, or faced being declared a "suppressive person" by the organization's management.[340] In March 2010, former Scientologist Janette Lang stated that at age 20 she became pregnant by her boyfriend while in the organization,[341] and her boyfriend's Scientology supervisors "coerced them into terminating the pregnancy".[342] "We fought for a week, I was devastated, I felt abused, I was lost and eventually I gave in. It was my baby, my body and my choice, and all of that was taken away from me by Scientology", said Lang.[342][343]

Australian Senator Nick Xenophon gave a speech to the Australian Parliament in November 2009, about statements he had received from former Scientologists.[344] He said that he had been told members of the organization had coerced pregnant female employees to have abortions.[344] "I am deeply concerned about this organisation and the devastating impact it can have on its followers," said Senator Xenophon, and he requested that the Australian Senate begin an investigation into Scientology.[344] According to the letters presented by Senator Xenophon, the organization was involved in "ordering" its members to have abortions.[345]

Former Scientologist Aaron Saxton sent a letter to Senator Xenophon stating he had participated in coercing pregnant women within the organization to have abortions.[346] "Aaron says women who fell pregnant were taken to offices and bullied to have an abortion. If they refused, they faced demotion and hard labour. Aaron says one staff member used a coat hanger and self-aborted her child for fear of punishment," said Senator Xenophon.[347] Carmel Underwood, another former Scientologist, said she had been put under "extreme pressure" to have an abortion,[348] and that she was placed into a "disappearing programme", after refusing.[349] Underwood was the executive director of Scientology's branch in Sydney.[347]

Scientology spokesman Tommy Davis said these statements are "utterly meritless".[338] Mike Ferriss, the head of Scientology in New Zealand, told media that "There are no forced abortions in Scientology".[350] Scientology spokesperson Virginia Stewart likewise rejected the statements and asserted "The Church of Scientology considers the family unit and children to be of the utmost importance and does not condone nor force anyone to undertake any medical procedure whatsoever."[351]

Allegation of human trafficking and other crimes against women

A number of women have sued the Church of Scientology, alleging a variety of complaints including human trafficking, rape, forced labor, and child abuse.[352] In 2009, two former Sea Org employees, Marc and Claire Headley, sued the Church of Scientology alleging human trafficking.[353]

Scientology, litigation, and the Internet

In the 1990s, Miscavige's organization took action against increased criticism of Scientology on the Internet and online distribution of Scientology-related documents.[354] Starting in 1991, Scientology filed fifty lawsuits against Scientology-critic Cult Awareness Network (CAN).[355] Many of the suits were dismissed, but one resulted in $2 million in losses, bankrupting the network.[355] At bankruptcy, CAN's name and logo were obtained by a Scientologist.[355][356] A New Cult Awareness Network was set up with Scientology backing, which says it operates as an information and networking center for non-traditional religions, referring callers to academics and other experts.[357][358]

In a 1993 U.S. lawsuit brought by the Church of Scientology against former member Steven Fishman, Fishman made a court declaration which included several dozen pages of formerly secret esoterica detailing aspects of Scientologist cosmogony.[359] As a result of the litigation, this material, normally strictly safeguarded and used only in Scientology's more advanced "OT levels", found its way onto the Internet.[359] This resulted in a battle between the Scientology organization and its online critics over the right to disclose this material, or safeguard its confidentiality.[359] The organization was forced to issue a press release acknowledging the existence of this cosmogony, rather than allow its critics "to distort and misuse this information for their own purposes".[359]

In January 1995, Church of Scientology lawyer Helena Kobrin attempted to shut down the newsgroup alt.religion.scientology by sending a control message instructing Usenet servers to delete the group.[360] In practice, this rmgroup message had little effect, since most Usenet servers are configured to disregard such messages when sent to groups that receive substantial traffic, and newgroup messages were quickly issued to recreate the group on those servers that did not do so. However, the issuance of the message led to a great deal of public criticism by free-speech advocates.[361][362] Among the criticisms raised, one suggestion is that Scientology's true motive is to suppress the free speech of its critics.[363][364]

The Church of Scientology also began filing lawsuits against those who posted copyrighted texts on the newsgroup and the World Wide Web, lobbied for tighter restrictions on copyrights in general, and supported the controversial Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act as well as the even more controversial Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Beginning in the middle of 1996 and ensuing for several years, the newsgroup was attacked by anonymous parties using a tactic dubbed sporgery by some, in the form of hundreds of thousands of forged spam messages posted on the group. Some investigators said that some spam had been traced to members of the Church of Scientology.[366][367] Former Scientologist Tory Christman later asserted that the Office of Special Affairs had undertaken a concerted effort to destroy alt.religion.scientology through these means; the effort failed.[368]

On January 14, 2008, a video produced by the Scientology organization featuring an interview with Tom Cruise was leaked to the Internet and uploaded to YouTube.[369][370][371] The Church of Scientology issued a copyright violation claim against YouTube requesting the removal of the video.[372] Calling the action by the Church of Scientology a form of Internet censorship, participants of Anonymous coordinated Project Chanology, consisting of a series of denial-of-service attacks against Scientology websites, prank calls, and black faxes to Scientology centers.[373][374][375][376]

On January 21, 2008, Anonymous announced its intentions via a video posted to YouTube entitled "Message to Scientology", and a press release declaring a "war" against the Church of Scientology and the Religious Technology Center.[377] In the press release, the group stated that the attacks against the organization would continue in order to protect the freedom of speech, and end what they saw as the financial exploitation of members of the organization.[378]

On January 28, 2008, an Anonymous video appeared on YouTube calling for protests outside Church of Scientology buildings on February 10, 2008.[379][380] The date was chosen because it was the birthday of Lisa McPherson.[381] According to a letter Anonymous e-mailed to the press, about 7,000 people protested in more than 90 cities worldwide.[382] Many protesters wore masks based on the character V from V for Vendetta (who was influenced by Guy Fawkes) or otherwise disguised their identities, in part to protect themselves from reprisals from the Church of Scientology.[383][384] Many further protests have followed since then in cities around the world.[385]

The Arbitration Committee of the Wikipedia internet encyclopedia decided in May 2009 to restrict access to its site from Church of Scientology IP addresses, to prevent self-serving edits by Scientologists.[386][387] A "host of anti-Scientologist editors" were topic-banned as well.[386][387] The committee concluded that both sides had "gamed policy" and resorted to "battlefield tactics", with articles on living persons being the "worst casualties".[386]

Disputes over legal status

The legal status of Scientology or Scientology-related organizations differs between jurisdictions.[31][32][388] Scientology was legally recognized as a tax-exempt religion in Australia,[33] Portugal,[389] and Spain.[390] Scientology was granted tax-exempt status in the United States in 1993.[391][392][393][394] The organization is considered a cult in Chile and an "anticonstitutional sect" in Germany,[36] and is considered a cult (French secte) by some French public authorities.[37]

The Church of Scientology argues that Scientology is a genuine religious movement that has been misrepresented, maligned, and persecuted.[262][395] The organization has pursued an extensive public relations campaign for the recognition of Scientology as a tax-exempt religion in the various countries in which it exists.[396][397][398]

The Church of Scientology has often generated opposition due to its strong-arm tactics directed against critics and members wishing to leave the organization.[399] A minority of governments regard it as a religious organization entitled to tax-exempt status, while other governments variously classify it as a business, cult, pseudoreligion, or criminal organization.[400][401]

In 1957, the Church of Scientology of California was granted tax-exempt status by the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and so, for a time, were other local branches of the organization.[35] In 1958 however, the IRS started a review of the appropriateness of this status.[188] In 1959, Hubbard moved to England, remaining there until the mid-1960s.[402] In 1967, the IRS removed Scientology's tax-exempt status, asserting that its activities were commercial and operated for the benefit of Hubbard, rather than for charitable or religious purposes.[35][403]

In the mid-sixties, the Church of Scientology was banned in several Australian states, starting with Victoria in 1965.[188] The ban was based on the Anderson Report, which found that the auditing process involved "command" hypnosis, in which the hypnotist assumes "positive authoritative control" over the patient. On this point the report stated:[3]: 115

It is the firm conclusion of this Board that most scientology and dianetic techniques are those of authoritative hypnosis and as such are dangerous ... the scientific evidence which the Board heard from several expert witnesses of the highest repute ... leads to the inescapable conclusion that it is only in name that there is any difference between authoritative hypnosis and most of the techniques of scientology. Many scientology techniques are in fact hypnotic techniques, and Hubbard has not changed their nature by changing their names.[3]: 115

The Australian branch of the Scientology organization was forced to operate under the name of the "Church of the New Faith" as a result, the name and practice of Scientology having become illegal in the relevant states. Several years of court proceedings aimed at overturning the ban followed.[33] In 1973, state laws banning Scientology were overturned in Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia. In 1983 the High Court of Australia ruled in a unanimous decision that the Church of Scientology was "undoubtedly a religion and deserving of tax exemption".[34]

Scientology in religious studies

Hugh B. Urban writes that "Scientology's efforts to get itself defined as a religion make it an ideal case study for thinking about how we understand and define religion."[404] Frank K. Flinn, adjunct professor of religious studies at Washington University in St. Louis wrote, "it is abundantly clear that Scientology has both the typical forms of ceremonial and celebratory worship and its own unique form of spiritual life."[405]

Flinn further states that religion requires "beliefs in something transcendental or ultimate, practices (rites and codes of behavior) that re-inforce those beliefs and, a community that is sustained by both the beliefs and practices", all of which are present within Scientology.[400] Similarly, World Religions in America states that "Scientology contains the same elements of most other religions, including myths, scriptures, doctrines, worship, sacred practices and rituals, moral and ethical expectations, a community of believers, clergy, and ecclesiastic organizations."[406] According to Mikhael Rothstein, Scientology's rituals can be classified into 1) those with the purpose of changing the person, such as auditing; 2) collective, which are calendar events where Scientology, its community and L. Ron Hubbard are celebrated; 3) rites of passage 4) weekly services that are similar to Christian services.[407]

While acknowledging that a number of his colleagues accept Scientology as a religion, sociologist Stephen A. Kent writes: "Rather than struggling over whether or not to label Scientology as a religion, I find it far more helpful to view it as a multifaceted transnational corporation, only one element of which is religious" [emphasis in the original].[6][40] Donna Batten in the Gale Encyclopedia of American Law writes, "A belief does not need to be stated in traditional terms to fall within First Amendment protection. For example, Scientology – a system of beliefs that a human being is essentially a free and immortal spirit who merely inhabits a body – does not propound the existence of a supreme being, but it qualifies as a religion under the broad definition propounded by the Supreme Court."[408]

A great number of research archives on Scientology have emerged in recent years for the academic study of Scientology. These include collections in San Diego State University, University of California, Santa Barbara, University of California, Los Angeles, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, Ohio State University and Claremont College Library. There is also a big collection of alternative beliefs and religions at the University of Alberta Library in Canada, where scholar Stephen A. Kent "makes material available on a restricted bases to undergraduate and graduate students."[409]

The material contained in the OT levels has been characterized as bad science fiction by critics, while others claim it bears structural similarities to gnostic thought and ancient Hindu beliefs of creation and cosmic struggle.[410] Donald A. Westbrook suggests that there are three areas of research scholars should consider researching and writing about: the biographical life and legacy of L. Ron Hubbard, the Church of Scientology's social betterment programs, and derivative scientology.[411]

Influences

The general orientation of Hubbard's philosophy owes much to Will Durant, author of the popular 1926 classic The Story of Philosophy; Dianetics is dedicated to Durant.[412] Hubbard's view of a mechanically functioning mind in particular finds close parallels in Durant's work on Spinoza.[412] According to Hubbard himself, Scientology is "the Western anglicized continuance of many early forms of wisdom".[413] Ankerberg and Weldon mention the sources of Scientology to include "the Vedas, Buddhism, Judaism, Gnosticism, Taoism, early Greek civilization and the teachings of Jesus, Nietzsche and Freud".[414]

Hubbard asserted that Freudian thought was a "major precursor" to Scientology. W. Vaughn Mccall, Professor and Chairman of the Georgia Regents University writes, "Both Freudian theory and Hubbard assume that there are unconscious mental processes that may be shaped by early life experiences, and that these influence later behavior and thought." Both schools of thought propose a "tripartite structure of the mind".[415] Sigmund Freud's psychology, popularized in the 1930s and 1940s, was a key contributor to the Dianetics therapy model, and was acknowledged unreservedly as such by Hubbard in his early works.[416] Hubbard never forgot, when he was 12 years old, meeting Cmdr. Joseph Cheesman Thompson, a U.S. Navy officer who had studied with Freud[417] and when writing to the American Psychological Association in 1949, he stated that he was conducting research based on the "early work of Freud".[418]

In Dianetics, Hubbard cites Hegel as a negative influence – an object lesson in "confusing" writing.[419] According to Mary A. Mann, Scientology is considered nondenominational, accepting all people regardless of their religions background, ethnicity, or educational attainment.[420] Another influence was Alfred Korzybski's General Semantics.[416] Hubbard was friends with fellow science fiction writers A. E. van Vogt and Robert Heinlein, who both wrote science-fiction inspired by Korzybski's writings, such as Vogt's The World of Null-A. Hubbard's view of the reactive mind has acknowledged parallels with Korzybski's thought; in fact, Korzybski's "anthropometer" may have been what inspired Hubbard's invention of the E-meter.[416]

Beyond that, Hubbard himself named a great many other influences in his own writing – in Scientology 8-8008, for example, these include philosophers from Anaxagoras and Aristotle to Herbert Spencer and Voltaire, physicists and mathematicians like Euclid and Isaac Newton, as well as founders of religions such as Buddha, Confucius, Jesus and Mohammed—but there is little evidence in Hubbard's writings that he studied these figures to any great depth.[416]

As noted, elements of the Eastern religions are evident in Scientology,[418] in particular the concept of karma found in Hinduism and Jainism.[421][422] In addition to the links to Hindu texts, Scientology draws from Taoism and Buddhism.[423] According to the Encyclopedia of Community, Scientology "shows affinities with Buddhism and a remarkable similarity to first-century Gnosticism".[424][425]

Demographics

As of 2016, scholarly estimates suggest that there are a maximum of 40,000 Scientologists;[57] this was the estimate given in 2011 by high-level Church of Scientology defector Jefferson Hawkins.[426] They are found mostly in the U.S., Europe, South Africa and Australia.[299]

By the start of the 21st century, the organization was claiming it had 8 million members.[65] Several commentators observe that this number is cumulative rather than collective: that is, it represents the total number of people who had any interaction with the Scientology organization since its founding, some of whom only had one or two auditing sessions.[427] The organization also maintained that it was the world's fastest growing religion,[428] a title also claimed by several religious groups, including Mormons, modern Pagans, and Baháʼí,[429] but which is demonstrably incorrect.[430][431][400][432][433] Due to its internationally dispersed nature, it is difficult to determine the number of Free Zone Scientologists.[434] In 2021, Thomas suggested that the Free Zone was growing,[434] with Lewis commenting that Free Zoners may one day outnumber members of the Church of Scientology.[435]

The American Religious Identification Survey of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York found 45,000 Scientologists in the United States in 1990,[430] and then 55,000 in 2001,[436] although in 2008 it estimated that that number had dropped to 25,000.[437][438] Lewis commented that the "pattern of solid growth" he observed in the 2000s seemed "suddenly to have ground to a halt" by the early 2010s.[439] Within the U.S., higher rates of Scientology have been observed in the western states, especially those bordering the Pacific Ocean, than further east.[440] The Canadian census revealed 1,215 Scientologists in 1991 and 1,525 in 2001,[218] down to 1,400 in 2021.[441] The Australian census reported 1,488 Scientologists in 1996 and 2,032 in 2001,[442] before dropping to under 1,700 in 2016.[443][444][445] The New Zealand census found 207 Scientologists in 1991 and 282 in 2001.[218] Andersen and Wellendorf estimated that there were between 2000 and 4000 Scientologists in Denmark in 2009,[446] with contemporary estimates suggesting between 500 and 1000 active Scientologists in Sweden.[447] Germany's government counted 3600 German members in 2021,[448] while observers have suggested between 2000 and 4000 in France.[208] The 2021 census in England and Wales recorded 1,800 Scientologists.[449]

Internationally, the Scientology organization's members are largely middle-class.[450] In Australia, Scientologists have been observed as being wealthier and more likely to work in managerial and professional roles than the average citizen.[451] Scientology is oriented towards individualistic and liberal economic values;[452] the scholar of religion Susan J. Palmer observed that Scientologists display "a capitalist ideology that promotes individualistic values".[453] A survey of Danish Scientologists revealed that nearly all voted for liberal or conservative parties on the right of Denmark's political spectrum and took a negative view of socialism.[454] Placing great emphasis on the freedom of the individual, those surveyed believed that the state and its regulations held people down, and felt that the Danish welfare system was excessive.[455] Interviewing Church members in the United States, Westbrook found that most regarded themselves as apolitical, Republicans, or libertarians; fewer than 10 percent supported the Democratic Party.[456]

Recruitment

Most people who join the organization are introduced to it via friends and family.[457] It also offers free "personality tests" or "stress tests", typically involving an E-Meter, to attract potential recruits.[458] It hopes that if non-Scientologists purchase one service from the Church and feel a benefit from it – a "win" in Church terminology – they are more likely to purchase additional services from the Church.[459] Other recruitment methods include lectures and classes introducing non-Scientologists to the subject.[207]

The Church of Scientology's own statistics, published in 1998, reveal that 52.6% of those who joined did so through their family and friendship networks with existing members.[460] 18% were drawn in through personality tests, 4.8% through publicity, and 3.1% through lectures.[461] Westbrook's interviews with Church members determined that most people who joined the Church were initially attracted by "the practical benefits advertised".[462] Westbrook found that various members deepened their involvement after having what they considered to be a spiritual experience, such as exteriorization or a past life memory, in their first few weeks of involvement.[463]

Reception and influence