Ostrich

| Ostrich | |

|---|---|

| |

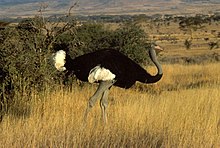

| Montage of two living species, from left to right: common ostrich and Somali ostrich | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | Struthioniformes |

| Family: | Struthionidae |

| Genus: | Struthio Linnaeus, 1758[1] |

| Type species | |

| Struthio camelus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Ostriches are large flightless birds. Two living species are recognised, the common ostrich, native to large areas of sub-Saharan Africa, and the Somali ostrich, native to the Horn of Africa.

They are the heaviest and largest living birds, with adult common ostriches weighing anywhere between 63.5 and 145 kilograms and laying the largest eggs of any living land animal.[3] With the ability to run at 70 km/h (43.5 mph),[4] they are the fastest birds on land. They are farmed worldwide, with significant industries in the Philippines and in Namibia. South Africa produces about 70% of global ostrich products,[5] with the industry largely centered around the town of Oudtshoorn. Ostrich leather is a lucrative commodity, and the large feathers are used as plumes for the decoration of ceremonial headgear. Ostrich eggs and meat have been used by humans for millennia. Ostrich oil is another product that is made using ostrich fat.

Ostriches are of the genus Struthio in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infraclass Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that includes the emus, rheas, cassowaries, kiwis and the extinct elephant birds and moas.

The common ostrich was historically native to the Arabian Peninsula, and ostriches were present across Asia as far east as China and Mongolia during the Late Pleistocene and possibly into the Holocene.

Taxonomic history

The genus Struthio was first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. The genus was used by Linnaeus and other early taxonomists to include the emu, rhea, and cassowary, until they each were placed in their own genera.[1] The Somali ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes) has recently become recognized as a separate species by most authorities, while others are still reviewing the evidence.[6][7]

Evolution

Struthionidae is a member of the Struthioniformes, a group of paleognath birds which first appeared during the Early Eocene, and includes a variety of flightless forms which were present across the Northern Hemisphere (Europe, Asia and North America) during the Eocene epoch. The closest relatives of Struthionidae within the Struthioniformes are the Ergilornithidae, known from the late Eocene to early Pliocene of Asia. It is therefore most likely that Struthionidae originated in Asia.[8]

The earliest fossils of the genus Struthio are from the early Miocene ~21 million years ago of Namibia in Africa, so it is proposed that genus is of African origin. By the middle to late Miocene (5–13 mya) they had spread to and become widespread across Eurasia.[9] While the relationship of the African fossil species is comparatively straightforward, many Asian species of ostrich have been described from fragmentary remains, and their interrelationships and how they relate to the African ostriches are confusing. In India, Mongolia and China, ostriches are known to have become extinct only around, or even after, the end of the last ice age; images of ostriches have been found prehistoric Chinese pottery and petroglyphs.[10][11][12][13]

-

Struthio camelus egg – MHNT

-

Size comparison (with a chicken egg and a US dollar bill)

-

Ostrich with eggs

Distribution and habitat

Today, ostriches are only found natively in the wild in Africa, where they occur in a range of open arid and semi-arid habitats such as savannas and the Sahel, both north and south of the equatorial forest zone.[14] The Somali ostrich occurs in the Horn of Africa, having evolved isolated from the common ostrich by the geographic barrier of the East African Rift. In some areas, the common ostrich's Masai subspecies occurs alongside the Somali ostrich, but they are kept from interbreeding by behavioral and ecological differences.[15] The Arabian ostriches in Asia Minor and Arabia were hunted to extinction by the middle of the 20th century, and in Israel attempts to introduce North African ostriches to fill their ecological role have failed.[16] Escaped common ostriches in Australia have established feral populations.[17][18][19]

Species

In 2008, S. linxiaensis was transferred to the genus Orientornis.[20] Three additional species, S. pannonicus, S. dmanisensis, and S. transcaucasicus, were transferred to the genus Pachystruthio in 2019.[21] Several additional fossil forms are ichnotaxa (that is, classified according to the organism's trace fossils such as footprints rather than its body) and their association with those described from distinctive bones is contentious and in need of revision pending more good material.[22]

The species are:

- Prehistoric

- †Struthio barbarus Arambourg 1979

- †Struthio brachydactylus Burchak-Abramovich 1939 (Pliocene of Ukraine)

- †Struthio chersonensis (Brandt 1873) Lambrecht 1921 (Pliocene of SE Europe to WC Asia) – oospecies

- †Struthio coppensi Mourer-Chauviré et al. 1996 (Early Miocene of Elizabethfeld, Namibia)

- †Struthio daberasensis Pickford, Senut & Dauphin 1995 (Early – Middle Pliocene of Namibia) – oospecies

- †Struthio kakesiensis Harrison & Msuya 2005 (Early Pliocene of Laetoli, Tanzania) – oospecies

- †Struthio karingarabensis Senut, Dauphin & Pickford 1998 (Late Miocene – Early Pliocene of SW and CE Africa) – oospecies(?)

- †Struthio oldawayi Lowe 1933 (Late Pleistocene of Tanzania) – probably subspecies of S. camelus[23]

- †Struthio orlovi Kuročkin & Lungo 1970 (Late Miocene of Moldavia)

- †Struthio wimani Lowe 1931 (Early Pliocene of China and Mongolia)

- Late Pleistocene – Holocene

- †Struthio anderssoni Lowe 1931, East Asian ostrich (Late Pleistocene of China to Mongolia)[11][12][24] –

- †Struthio asiaticus Brodkorb 1863, Asian ostrich (Early Pliocene – Early Holocene of Central Asia to China? and Morocco)

- Struthio camelus, common ostrich

- Struthio molybdophanes, Somali ostrich

Citations

- ^ a b Gray, George Robert (1855). Catalogue of the Genera and Subgenera of Birds contained in the British Museum. London, UK: Taylor and Francis. p. 109.

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Struthio camelus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T45020636A132189458. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T45020636A132189458.en. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Del Hoyo, Josep, et al. Handbook of the birds of the world. Vol. 1. No. 8. Barcelona: Lynx edicions, 1992.

- ^ Doherty, James G. (March 1974). "Speed of animals". Natural History.

- ^ Western Cape Department of Agriculture (July 2020). "The South African Ostrich Industry Footprint" (PDF). Retrieved 20 May 2024.

- ^ Gill, F.; Donsker, D (2012). "Ratites". IOC World Bird List. WorldBirdNames.org. Retrieved 13 Jun 2012.

- ^ BirdLife International (2012). "The BirdLife checklist of the birds of the world, with conservation status and taxonomic sources". Archived from the original (xls) on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 16 Jun 2012.

- ^ Mayr, Gerald; Zelenkov, Nikita (2021-11-13). "Extinct crane-like birds (Eogruidae and Ergilornithidae) from the Cenozoic of Central Asia are indeed ostrich precursors". Ornithology. 138 (4): ukab048. doi:10.1093/ornithology/ukab048. ISSN 0004-8038.

- ^ Mikhailov, Konstantin E.; Zelenkov, Nikita (September 2020). "The late Cenozoic history of the ostriches (Aves: Struthionidae), as revealed by fossil eggshell and bone remains". Earth-Science Reviews. 208: 103270. Bibcode:2020ESRv..20803270M. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2020.103270. S2CID 225275210.

- ^ Doar, B.G. (2007) "Genitalia, Totems and Painted Pottery: New Ceramic Discoveries in Gansu and Surrounding Areas" Archived 2020-09-23 at the Wayback Machine. China Heritage Quarterly

- ^ a b Janz, Lisa; et al. (2009). "Dating North Asian surface assemblages with ostrich eggshell: Implications for palaeoecology and extirpation". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (9): 1982–1989. Bibcode:2009JArSc..36.1982J. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.05.012.

- ^ a b Andersson, Johan Gunnar (1923). On the occurrence of fossil remains of Struthionidae in China. In: Essays on the cenozoic of northern China. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of China (Peking), Series A, No. 3, pp. 53–77. Peking, China: Geological Survey of China.

- ^ Jain, Sonal; Rai, Niraj; Kumar, Giriraj; Pruthi, Parul Aggarwal; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Bajpai, Sunil; Pruthi, Vikas (2017-03-08). Calafell, Francesc (ed.). "Ancient DNA Reveals Late Pleistocene Existence of Ostriches in Indian Sub-Continent". PLOS ONE. 12 (3): e0164823. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1264823J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164823. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5342186. PMID 28273082.

- ^ Donegan, Keenan (2002). "Struthio camelus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

- ^ Freitag, Stephanie & Robinson, Terence J. (1993). "Phylogeographic patterns in mitochondrial DNA of the Ostrich (Struthio camelus)" (PDF). The Auk. 110 (3): 614–622. doi:10.2307/4088425. JSTOR 4088425.

- ^ Rinat, Zafrir (25 December 2007). "The Bitter Fate of Ostriches in the Wild". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- ^ Ostriches in Australia – and near my home Archived 2020-06-11 at the Wayback Machine. trevorsbirding.com (13 September 2007)

- ^ Rural, A. B. C. (2018-09-01). "The outback ostriches — Australia's loneliest birds". ABC News. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ "Common Ostrich (Struthio camelus)". iNaturalist Australia. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- ^ Wang, S. (2008). "Rediscussion in the taxonomic assignment of Struthio linxiaensis Hou, et al., 2005". Acta Paleotologica Sinica. 47: 362–368.

- ^ Zelenkov, N. V.; Lavrov, A. V.; Startsev, D. B.; Vislobokova, I. A.; Lopatin, A. V. (2019). "A giant early Pleistocene bird from eastern Europe: unexpected component of terrestrial faunas at the time of early Homo arrival". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 39 (2): e1605521. Bibcode:2019JVPal..39E5521Z. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1605521. S2CID 198384367.

- ^ Bibi, Faysal; Shabel, Alan B.; Kraatz, Brian P.; Stidham, Thomas A. (2006). "New Fossil Ratite (Aves: Palaeognathae) Eggshell Discoveries from the Late Miocene Baynunah Foramation of the United Arab Emirates, Arabian Peninsula" (PDF). Palaeontologia Electronica. 9 (1): 2A. ISSN 1094-8074.

- ^ "OVPP-Struthio 8". olduvai-paleo.org.

- ^ Andersson, Johan Gunnar (1943). "Research into the prehistory of the Chinese". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 15: 1–300.

General references

- Andersson, Johan Gunnar (1943). "Researches into the prehistory of the Chinese". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 15: 1–300, plus 200 plates.

- Brands, Sheila (14 Aug 2008). "Taxon: Genus Struthio". Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved 12 Jun 2012.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003). "Ostriches". In Hutchins, Michael (ed.). Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Vol. 8 (2nd ed.). Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7876-5784-0.

- Hou, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z. (Aug 2005). "A Miocene ostrich fossil from Gansu Province, northwest China". Chinese Science Bulletin. 50 (16): 1808–1810. Bibcode:2005ChSBu..50.1808H. doi:10.1360/982005-575 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISSN 1861-9541. S2CID 129449364.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - Janz, Lisa; et al. (2009). "Dating North Asian surface assemblages with ostrich eggshell: Implications for palaeoecology and extirpation". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (9): 1982–1989. Bibcode:2009JArSc..36.1982J. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.05.012.

- "Seagull Publishers:: K-8 segment | Books | Practice manuals". Seagull Learning – A Unit of Seagull Publishers Private Limited. 7. 20 July 2023.