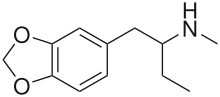

MBDB

| |

Chemical structure | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Methylbenzodioxolyl-butanamine; N-Methyl-1,3-benzodioxolylbutanamine; MBDB; 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methyl-butanphenamine; MDMB; 1,3-Benzodioxolyl-N-methylbutanamine; BDMB; 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methyl-α-ethylphenylethylamine; 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methyl-α-desmethyl-α-ethylamphetamine; Eden; Methyl-J |

| Drug class | Serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agent; Empathogen–entactogen |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Duration of action | 4–6 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C12H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 207.273 g·mol−1 |

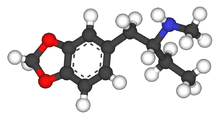

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 156 °C (313 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

MBDB, also known as N-methyl-1,3-benzodioxolylbutanamine or as 3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methyl-α-ethylphenylethylamine, is an entactogen of the phenethylamine, amphetamine, and phenylisobutylamine families related to MDMA.[1][2][3][4] It is known by the street names "Eden" and "Methyl-J".[4]

History and effects

[edit]MBDB was first synthesized by pharmacologist and medicinal chemist David E. Nichols[citation needed] and later tested by Alexander Shulgin and described in his book, PiHKAL: A Chemical Love Story. MBDB's dosage, according to PiHKAL, is 180 to 210 mg; the proper dosage relative to body mass seems unknown.[1] Its duration is 4 to 6 hours, with noticeable after-effects lasting for 1 to 3 hours.[1][additional citation(s) needed]

MBDB was initially developed as a non-psychedelic entactogen. It has lower effects on the dopamine system in comparison to other entactogens such as MDMA.[citation needed] MBDB causes many mild, MDMA-like effects, in particular the lowering of social barriers and inhibitions, pronounced sense of empathy and compassion, and mild euphoria, all of which are present.[citation needed] MBDB tends to produce less euphoria, psychedelia, and stimulation in comparison to MDMA.[citation needed]

Clinical studies have found that MBDB produces similar entactogenic effects to MDMA, but lacks psychedelic and stimulant effects.[1][2] It enhances mood similarly to MDMA, but lacks the pronounced euphoria of MDMA.[1] MBDB produces prosocial effects similarly to MDMA, although it is said to be moderately less effective.[1]

Chemistry

[edit]MBDB is a ring substituted amphetamine and an analogue of MDMA. Like MDMA, it has a methylenedioxy substitution at the 3 and 4 position on the aromatic ring; this is perhaps the most distinctive feature that structurally define analogues of MDMA, in addition to their unique effects, and as a class they are often referred to as "entactogens" to differentiate between typical stimulant amphetamines that (as a general rule) are not ring substituted. MBDB differs from MDMA by having an ethyl group instead of a methyl group attached to the alpha carbon; all other parts are identical. Modification at the alpha carbon is uncommon for substituted amphetamines.

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]MBDB acts as a serotonin–norepinephrine releasing agent (SNRA).[1][2][5] Its EC50 values for induction of monoamine release are 540 nM for serotonin, 3,300 nM for norepinephrine (6.1-fold lower than for serotonin), and >100,000 for dopamine (>185-fold lower than for serotonin).[5] However, it may still have slight dopamine-releasing actions.[2] MBDB fully substitutes for MDMA in drug discrimination tests in rodents.[1][2] It increases locomotor activity similarly to but less robustly than MDMA.[6] Likewise, MBDB increases conditioned place preference (CPP) similarly but less efficaciously than MDMA.[2] In contrast to MDMA, which produced hyperthermia, MBDB instead produced dose- and time-dependent hypothermia.[6]

MBDB has similar affinities for the serotonin 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors as MDMA.[1][7] However, MBDB did not show the head-twitch response, a behavioral proxy of psychedelic effects, at any dose in rodents.[6] In addition, MBDB (as well as MDMA) do not substitute for lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in drug discrimination tests.[2] The lack of apparent hallucinogenic effects with MBDB is analogous to the case of Ariadne, the α-ethyl homologue of DOM; (R)-Ariadne (BL-3912A) showed no psychedelic effects in humans at doses of up to 270 mg orally, whereas DOM is active as a hallucinogen at doses of 5 to 10 mg orally.[7][8] This may be due to lower activational efficacy at the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[8]

MBDB is a serotonergic neurotoxin similarly to MDMA.[1][2][9] However, MBDB appears to have reduced serotonergic neurotoxicity compared to MDMA at behaviorally equivalent doses.[1][2][9][3] In addition, unlike MDMA, MBDB does not produce dopaminergic neurotoxicity in mice.[9]

MBDB and its individual enantiomers, (S)-MBDB and (R)-MBDB, show similar behavioral effects in animals.[6]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]The metabolism of MBDB has been described in the scientific literature.[10]

Legal status

[edit]Unlike MDMA, MBDB is not internationally scheduled under the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances. The thirty-second meeting of the WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (September 2000) evaluated MBDB and recommended against scheduling.[11] From the WHO Expert Committee assessment of MBDB:

- Although MBDB is both structurally and pharmacologically similar to MDMA, the limited available data indicate that its stimulant and euphoriant effects are less pronounced than those of MDMA. There have been no reports of adverse or toxic effects of MBDB in humans. Law enforcement data on illicit trafficking of MBDB in Europe suggest that its availability and abuse may now be declining after reaching a peak during the latter half of the 1990s. For these reasons, the Committee did not consider the abuse liability of MBDB would constitute a significant risk to public health, thereby warranting its placement under international control. Scheduling of MBDB was therefore not recommended.

Australia

[edit]MBDB is considered a Schedule 9 Prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[12] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[12]

Finland

[edit]Scheduled in the "government decree on psychoactive substances banned from the consumer market".[13]

Russia

[edit]MBDB is included into Schedule 1 of the Controlled Substances Act.[14]

Sweden

[edit]Sveriges riksdags health ministry Statens folkhälsoinstitut [sv] classified MBDB as "health hazard" under the act Lagen om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor [sv] (translated Act on the Prohibition of Certain Goods Dangerous to Health) as of Feb 25, 1999, in their regulation SFS 1999:58 listed as "2-metylamino-1-(3,4-metylendioxifenyl)-butan (MBDB)", making it illegal to sell or possess.[15]

Research

[edit]MBDB is being assessed by PharmAla Biotech for potential medical use as a pharmaceutical drug, for instance to treat autism.[7][16][17][6]

See also

[edit]- Ethylbenzodioxolylbutanamine (EBDB; Ethyl-J)

- Methylbenzodioxolylpentanamine (MBDP; Methyl-K)

- UWA-101

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Oeri HE (May 2021). "Beyond ecstasy: Alternative entactogens to 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine with potential applications in psychotherapy". J Psychopharmacol. 35 (5): 512–536. doi:10.1177/0269881120920420. PMC 8155739. PMID 32909493.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Aerts LA, Mallaret M, Rigter H (July 2000). "N-methyl-1-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-2-butanamine (MBDB): its properties and possible risks". Addict Biol. 5 (3): 269–282. doi:10.1111/j.1369-1600.2000.tb00191.x. PMID 20575841.

- ^ a b Nichols DE, Marona-Lewicka D, Huang X, Johnson MP (1993). "Novel serotonergic agents". Drug des Discov. 9 (3–4): 299–312. PMID 8400010.

- ^ a b "MBDB". Erowid Center.

- ^ a b Nagai F, Nonaka R, Satoh Hisashi Kamimura K (March 2007). "The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain". Eur J Pharmacol. 559 (2–3): 132–137. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.075. PMID 17223101.

- ^ a b c d e Clark MR, Shaw HE, Fantegrossi WE (March 2024). Poster 21: In vivo characterization of MBDB and its enantiomers in C57BL/6 and autism-like BTBR T+Itpr3tf/J mice (PDF). 16th Annual Behavior, Biology, and Chemistry: Translational Research in Substance Use Disorders, San Antonio, Texas, Embassy Landmark, 22-24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Kaur H, Karabulut S, Gauld JW, Fagot SA, Holloway KN, Shaw HE, Fantegrossi WE (2023). "Balancing Therapeutic Efficacy and Safety of MDMA and Novel MDXX Analogues as Novel Treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder". Psychedelic Medicine. 1 (3): 166–185. doi:10.1089/psymed.2023.0023.

Author Disclosure Statement: H.K. is Vice President of Research at PharmAla Biotech and is listed as an inventor on patents related to the research in this review article. H.E.S. receives salary supported from a contract between PharmAla Biotech and UAMS. W.E.F. receives research funds and salary support from a contract between PharmAla Biotech and UAMS. The other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

- ^ a b Cunningham MJ, Bock HA, Serrano IC, Bechand B, Vidyadhara DJ, Bonniwell EM, Lankri D, Duggan P, Nazarova AL, Cao AB, Calkins MM, Khirsariya P, Hwu C, Katritch V, Chandra SS, McCorvy JD, Sames D (January 2023). "Pharmacological Mechanism of the Non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A Agonist Ariadne and Analogs". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 14 (1): 119–135. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00597. PMC 10147382. PMID 36521179.

- ^ a b c Johnson MP, Nichols DE (May 1989). "Neurotoxic effects of the alpha-ethyl homologue of MDMA following subacute administration". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 33 (1): 105–108. doi:10.1016/0091-3057(89)90437-1. PMID 2476831.

- ^ Lai FY, Erratico C, Kinyua J, Mueller JF, Covaci A, van Nuijs AL (October 2015). "Liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for screening in vitro drug metabolites in humans: investigation on seven phenethylamine-based designer drugs" (PDF). Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 114: 355–75. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2015.06.016. hdl:10067/1278220151162165141. PMID 26112925.

- ^ WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence (2001). "Thirty-second Report, Technical Report Series 903" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Poisons Standard". Federal Register of Legislation. Australian Government. October 2015.

- ^ https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2014/20141130

- ^ ru:MBDB[circular reference]

- ^ "Svensk författningssamling" [Swedish Code of Statutes] (PDF) (in Swedish). Notisum AB. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-06. Retrieved 2013-09-25.

- ^ PharmAla Biotech (23 February 2023). "Patent Application Published for PharmAla Biotech's MDMA Analogs". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- ^ PharmAla Biotech (26 March 2024). "PharmAla Biotech Signs Sale Agreement with Numinus". GlobeNewswire News Room (Press release). Retrieved 10 November 2024.